The Web History Part-One: From Netscape to Google and Beyond! [Special Edition]

If you want to understand what’s going on next in AI, we have to take a few steps back and look at the whole evolution of the web. From there, I’ll show you where we’re headed next.

But before, let me tell you how the commercial internet developed, from walled gardens to the open web and back to walled gardens!

In this piece, I’ll lead you through the journey from the first to the third wave of the web.

And I’ll leave it up to the next piece to show you what’s happening in the fourth wave of the web!

First Wave (1994–1999): The Walled Gardens

Key Players: AOL, Prodigy, CompuServe, GEnie

Characteristics:

Controlled, proprietary networks offering limited online services (email, forums, news).

Subscription-based models with limited hours and pay-per-use for extra access.

Major Events:

AOL became a dominant player, peaking in 1999 with a $200 billion valuation.

AOL acquired Netscape in 1998 and merged with Time Warner in 2000.

Limitations:

Closed ecosystems stifled innovation and failed to adapt to open web protocols.

Growth of broadband and open standards led to the decline of proprietary networks.

Second Wave (1999–2005): Web 1.0 and the Rise of Browsers

Key Players: Netscape, Microsoft (Internet Explorer), Google (emerging)

Characteristics:

Transition from proprietary networks to open web browsing.

The browser wars between Netscape and Microsoft shaped access to the web.

Search engines began to surface as tools for navigating the exponentially growing web.

Major Events:

Netscape IPO in 1995 created the first billion-dollar Internet startup.

Microsoft bundled Internet Explorer with Windows, dominating the browser market.

Google launched in 1998, leveraging PageRank to rank web pages organically.

Outcomes:

Browsers democratized web access, breaking down the walls of proprietary networks.

Search became essential for navigating the growing web, paving the way for Web 2.0.

Third Wave (2005–2015): Web 2.0 and the Platform Economy

Key Players: Google, Facebook, YouTube, Amazon, Twitter

Characteristics:

Shift from static web pages to interactive, user-generated content and social networks.

The rise of platforms leveraging network effects and data-driven business models.

Advertising became the dominant revenue model (e.g., Google AdWords, Facebook Ads).

Major Events:

Google acquired YouTube in 2006 and developed AdSense to monetize web traffic.

Social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter transformed online interaction.

Mobile web gained traction with the advent of smartphones.

Outcomes:

Platforms became the new gatekeepers of the web, creating walled gardens of their own.

Data and user engagement became central to monetization strategies.

Fourth Wave (2015–Present): AI-Driven and Task-Oriented Web

Key Players: Google (Alphabet), OpenAI, Microsoft, Amazon Web Services (AWS)

Characteristics:

AI and machine learning integrate deeply into web services (e.g., Google Assistant, ChatGPT).

Shift from "finding information" to "getting things done" through AI tools.

Growth of semantic web and knowledge graphs to structure and contextualize data.

Major Events:

Google’s "AI-first" strategy (2017) incorporated AI into products like Google Photos, Translate, and Home.

OpenAI released GPT models, with ChatGPT reaching massive global adoption by 2024.

Expansion of decentralized and blockchain-based technologies hinting at Web 3.0.

Outcomes:

AI reshapes how users interact with the web, emphasizing automation and task efficiency.

Questions of data privacy, bias, and centralized control challenge dominant tech giants.

Also new players are completely reshaping the whole space!

Let’s start from the beginning of it all!

Read also

Currently, the predominant business model for commercial search engines is advertising. The goals of the advertising business model do not always correspond to providing quality search to users.

In 1998, in a paper entitled "The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine," Brin and Page, two Ph.D. students at Stanford University, expressed their frustration with the current search landscape.

Just a couple of years before, in 1996, the two students, working on an algorithm - called "BackRub" - leveraging backlinks (web links that looked like citations, where the site linked through a backlink gained authority over others, similarly to the citation mechanism in academia) managed to tame the exponentially growing web of pages.

By 1998, that project had become a company called Google.

Before we get to the story of what would later become Google, let's explore the context of these years and what the web (or the commercial Internet) looked like.

And how the various waves of the Internet were shaped by these companies.

The first internet wave and the first walled gardens

In the first wave of the commercial Internet (1994-1999), the first big tech players and tech giants were walled gardens. Those platforms enabled access to proprietary networks (this wasn’t the Internet, as those were not open protocols).

Instead, they were places where users could enjoy controlled and closed online services (emails, news, forums, and later search).

These first tech giants were AOL, Prodigy, CompuServe, and GEnie.

Their business model was straightforward: you would pay for a monthly subscription and enjoy a few hours of access to their proprietary networks. Each additional hour users spend on top of the subscription would be charged based on consumption.

The first Internet giant: AOL

AOL is a web portal and online service provider founded in 1983 by Marc Seriff, Steve Case, Jim Kimsey, and William von Meister.

AOL was one of the largest media companies of the early Internet, dominating email, internet connectivity, online news, and chat.

At its peak in 1999, AOL's market capitalization exceeded $200 billion.

As we'll see, this milestone happened as AOL acquired Netscape in its attempt to fully convert to the new rising wave of Web 1.0, which involves browsing first and then searching the commercial Internet.

Before closing this circle, let me give you some more context about these years.

AOL had mastered the art of attracting and then monetizing dial-up subscribers.

By the mid-90s, subscription business models, leveraging proprietary networks, had started fierce competition.

Thus, eventually, AOL was also forced to adopt an unlimited subscription plan. Indeed, in October 1996, at the peak of its popularity, AOL announced a $19.95 flat-rate pricing plan for unlimited access to both the Internet and AOL's private network.

As the legendary Steve Case announced at the time:

You're seeing a much more aggressive America Online. AOL in one fell swoop is trying to meet the needs of the mainstream and also address the concerns of Wall Street. We really repriced the service to reach out to the heavy users who really want and need unlimited pricing [and] the light users who want the comfort of a relatively low monthly fee.

Yet AOL's infrastructure was unprepared for the boom in popularity of broadband internet, and it barely handled that traffic, to the point that the platform started to crash more and more often.

By 1998, AOL was experiencing a set of outages that made the service more and more unreliable.

This also triggered class actions against the company as users got angrier.

This showed that the Internet was becoming a critical utility to users who subscribed to AOL and that AOL itself had become an important part of their lives.

Yet, the company had to start increasing its subscription plans, as the infrastructure was collapsing under the weight of additional traffic.

As the company peaked in 1998, Steve Case announced, " We're not going to get complacent, but we've created a service that's fun and easy to use. Those factors and the general shift in spending to new media position AOL as the best brand in the industry."

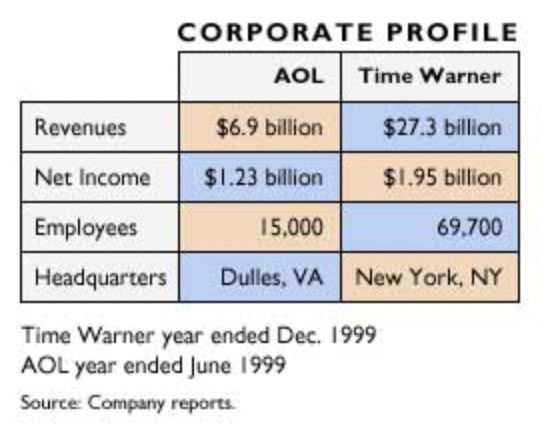

By the year 2000, AOL had generated over $6.8 billion, comprising subscription services ($4.4 billion), advertising/commerce (almost $2 billion), and $500 million from enterprise solutions.

By June 2000, AOL had 23.2 million members!

Take into account that in the US, in the year 2000, there were over 120 million Internet users, thus still making AOL the primary avenue to the Internet.

In the same year, AOL sealed the largest merger in United States history - after the Vodafone-Mannesmann merger, which reshaped the whole mobile telecom industry - which would play a key role in shaping the Internet as we know it.

In 2000, AOL acquired Time Warner for $111 billion. The result was a $360 billion multimedia conglomerate comprised of Time Warner’s vast media empire and AOL’s 30 million dial-up Internet subscribers.

As CNN Money highlighted back then, the deal was so big that it also worried Microsoft, which, as the merger was going through, started to engage with the Federal Trade Commission to restrict the deal and block it because it claimed it would restrict competition on the Internet.

It's critical—as we'll see—to understand that AOL had been helping regulators prepare the Microsoft antitrust case in the early 2000s; thus, Microsoft was looking for revenge.

Yet, the deal went through, but it set a condition:

AOL Time Warner must offer its subscribers the option to sign up to at least one nonaffiliated cable, high-speed Internet service provider via Time Warner's cable system before AOL itself begins offering such service.

In short, while AOL could merge with Time Warner, it still had to guarantee open access to the Internet to prevent it from becoming only a proprietary network controlled by the newly formed giant.

Unfortunately, the merger occurred just three months before the dot-com bubble burst, causing the economy to fall into a recession.

The relationship between Time Warner and AOL was often acrimonious. This hindered AOL’s ability to make serious inroads into broadband, which was then largely controlled by cable companies.

In the years following the merger, the dot-com recession and a lack of broadband integration lead to a severe decline in AOL subscribers.

AOL and Time Warner were two fundamentally different companies. AOL was primarily an online player, whereas Time Warner had tried but failed to enter the space.

The envisioned synergies between the two giants did not materialize, and these two companies never really managed to get along and create a unified culture. This also was a critical lesson in business history.

It doesn't matter how much firepower you have; sometimes, to dominate a new industry, you need to completely change the business playbook. AOL soon learned this lesson, which would cost it its leadership while new startups, like Google, would take over.

In 2003, AOL Time Warner posted an almost $100 billion loss – at the time the largest in U.S. corporate history. The dot-com bubble had crashed the valuation of the newly formed company.

In the meantime, by 2003, Google had become a web giant. When it presented its financials, the tech industry was taken aback by its incredible success.

Google was profitable and a rocket ship, generating almost a billion in revenue in 2003, with a net profit of over $106 million.

Before we get into the incredible rise of Google, we need to take another step back.

Indeed, you can hardly understand a search if you don't grasp the "browser wars" of the 1990s!

The fall of proprietary networks, the browser wars, and the rise of Web 1.0

As AOL took over the Internet in the first wave of the mid-90s, it also opened up its platform to more and more people by changing its revenue model. From the subscription and consumption model, AOL had to adapt to the unlimited subscription model, where users could enjoy unlimited access to AOL’s proprietary network.

Founded in 1983, AOL became the first web Internet giant, using a “walled-garden business strategy.”

By early 2000, this strategy had become obsolete since players like Google wrecked these walls off!

On paper, the merger of AOL and Time Warner formed a large and powerful company with the right mix of assets, but by the early 2000s, AOL had already lost most of its value.

With this new model, the AOL user base grew even further. However, it also showed some of its weaknesses, as the platform became unstable with many new members.

During this period, the Internet also grew exponentially, favoring the birth of a few tech players. Something very counterintuitive happened. Search, which seemed a feature to offer on top of the proprietary networks, became a killer commercial application!

How did search become a commercial killer application? The browser market had laid the foundation for the search market to thrive.

When Microsoft spent billions to bring TV online - the complete failure of the Information Superhighway

Grasping how new industries will evolve is one of the most difficult aspects of high-tech business.

Even the smartest people who dominate an industry can hardly imagine what the future will look like.

This is the reality of the business world. Indeed, back in the mid-90s, when the commercial Internet was finally taking over, most luminaries, gurus, and tech experts projected it as a sort of Information Superhigly (similarly to how today we talk about the Metaverse and how Mark Zuckerberg's vision for it might turn to be completely off).

As you can see, the vision, at the time, was about an "interactive entertainment center."

By 1995, Microsoft had tried to rewrite business history, as if Bill Gates and his company had fully grasped the Internet phenomenon. In reality, things looked quite different!

As explained by Jim Clark (co-founder of Netscape) in his book "Netscape Time: The Making of the Billion-Dollar Start-Up That Took on Microsoft," in 1994, Netscape was launching the browser that would conquer the whole browser market share, thus becoming, for a short period, the Internet!

In the same year, Microsoft was still trying to figure things out. Microsoft, a native player of the PC era, had risen during the 1970s when Intel had created a whole new industry.

Thanks to Intel's family of chips, the computer industry was born with the development of the 8080 - led by Federico Faggin - from now on.

As we saw, the turning point for Microsoft came when IBM was about to launch its personal Computer in 1980. Contrary to what IBM had done throughout its history, the IBM Personal Computer followed an open architecture.

In 1980, Microsoft partnered with IBM to bundle its operating system with IBM computers. The deal was straightforward: IBM would pay Microsoft $430,000 for what would be called MS-DOS.

Microsoft on the other hand could license that same operating system to other PC makers, beyond IBM. The microcomputer space, which in the late 1970s was dominated by Tandy, Commodore, and Apple, was taken by surprise as the IBM Personal Computer became a huge success.

Yet, by the early 1990s, IBM had lost its leadership and had failed to capture the value of the PC market.

On the other hand, Microsoft became the de facto operating system of the PC industry and became a tech giant within a decade.

In 1982, Microsoft recorded over $24 million in revenues, over $140 million in 1985, and by 1990, it had passed a billion dollars in revenue, the first tech company to do so, and had become the de facto operating system of the PC market.

Where IBM had created the PC standard in the early 1980s, Microsoft surfed it for decades!

Where IBM lost its leadership, the PC became a standard that would last for decades, spurring a market that gave rise to new players competing on price.

The hardware had been commoditized, and software, first in the form of the operating system and then applications, would be monetized at a premium.

Microsoft followed a platform strategy. On top of the operating system, it added applications (the first launch of Microsoft Office 1.0 happened in November 1990, and it comprised three applications: Word, Excel, and PowerPoint). Over the years, Microsoft bundled everything up, creating de facto the dominant operating system and PC applications provider in the world.

Its distribution power got so strong, that by the year 2000, Microsoft had a 96% market share of all PCs! Microsoft had mastered this platform strategy, which the new Internet players would soon use.

IBM's mistake would become one of the most studied in the history of high-tech business. As David Bradley, one of the teams of 12 who produced the PC at IBM, highlighted:

At the time, we didn't think it was going to be a revolutionary change, we knew we were working on an exciting project and we certainly hoped it was going to be successful, but we never imagined it was going to take over the world the way it did.

In short, IBM grasped the project's importance but missed its revolutionary potential. That is fine because, in hindsight, it's hard to determine which projects will become new industries.

However, IBM, which was still a big corporation at the time (they called it "Big Blue"), first approached a young Bill Gates in July 1980 (he was 24 at the time) to develop an operating system for what became the IBM Personal Computer.

Why did they do it? First, IBM was in a rush. In fact, back then, typical product cycles lasted four years. Instead, IBM wanted to bring the PC to market as quickly as possible.

In addition, IBM was playing a different game. For IBM at the time, it wasn't about the software; it was about the hardware. Indeed, back then, the software industry didn't exist, as software was treated as a commodity that was given for free on top of hardware.

Microsoft successfully commercialized software.

This mindset and philosophy stayed in Microsoft's culture for decades (the mantra for Microsoft under Bill Gates was "We are a software company"), so much so that when Microsoft tried to manufacture an alternative to the iPhone (its Windows Phone) in the 2010s, it failed miserably.

On the one hand, IBM had a team of 12 technical people working on the project and a legal and procurement team, while Bill Gates and Paul Allen were mostly doing things on their own.

As Bill Gates highlighted, remembering those days, "we had to be very clever. We actually did not get a royalty from IBM, but we kept the rights, so we were getting royalties from other people."

By 1993, IBM shocked the business world by reporting quarterly losses of $8bn, primarily caused by increased competition and a changing market. IBM had created a whole new industry, yet it had failed miserably in dominating and profiting from it. Microsoft, on the other hand, had become the scariest tech giant of the 1990s.

Also, other players like Apple, which had dominated the computer industry in the late 1970s (though computers were still for niches), refused to license its operating system to others, thus making Microsoft the uncontested PC standard for decades!

Anyone trying to enter the software space was a threat to Microsoft and, therefore, was to be killed as quickly as possible, as any potential new sub-industry that would be created in software, which Bill Gates could not control, needed to be suppressed or taken over by Microsoft.

In 1994-95, the Internet was the industry that Microsoft needed to dominate if it wanted to maintain its long-term dominance!

The interesting part was that some of these Internet competitors would use Microsoft's platform strategy to take over this new market.

#The commercial killer application of the early Internet: Browsing

Accessing the web in the early 1990s wasn't an easy fit. If it wasn't for proprietary networks like AOL, accessing the Internet in the first place would be very, very hard.

Mosaic, the first web browser, changed that! For the first time, users could access the Internet with a very simple and straightforward setup.

The browser was developed by an intelligent group of very young developers at NCSA. NCSA, or the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, was a research project unit set up at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

As the story goes, in 1992, Joseph Hardin and Dave Thompson, who worked at the NCSA, learned about Tim Berners-Lee's work at CERN.

In the fall of 1990, Tim Berners-Lee developed the first browser on a NeXT machine (the company Steve Jobs had created after being ousted from Apple) and an editor to create hypertext documents.

Text-based browsers started to emerge, and by 1992, Joseph Hardin and Dave Thompson downloaded the ViolaWWW browser, which had some extended functionalities compared to the first browsers.

Two students at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina, started to work on a new browser for X-Windows on Unix computers, releasing the first version in 1993.

This browser was called Mosaic, and it was the first browser to allow images embedded in the text, thus making for the first time, the Internet, way more interactive.

Yet, by August 1994, rather than enabling the development team to take over the project and commercialize it (as Stanford had been doing for decades), NCSA took over the Mosaic project, and it assigned its commercial rights to Spyglass, a corporation formed to profit from the Mosaic browser (in 1995, to kick off the launch of Internet Explorer and to kill Netscape's dominance, Microsoft licensed Spyglass’ Mosaic technology).

In this context, in early 1994, Jim Clark, an entrepreneur who had left his previous company, Silicon Graphics, was looking to create his next big thing. He was also looking for revenge, as he, the founder of Silicon Graphics, had become a marginal player within the company and barely managed to make a tiny fortune compared to the multi-billion dollar success he had built.

Jim Clark also considered the Internet a potential new business frontier. Like Bill Gates, he initially considered bringing TV online. Little did he know that shortly after, he would meet Marc Andreessen, the young kid behind the development of Mosaic.

At the same time, Microsoft and its founder, Bill Gates, understood the importance of the internet. Back in January 1996, Bill Gates wrote one of the most quoted pieces, still nowadays, “Content is King:”

One of the exciting things about the Internet is that anyone with a PC and a modem can publish whatever content they can create. In a sense, the Internet is the multimedia equivalent of the photocopier. It allows material to be duplicated at low cost, no matter the size of the audience.

Yet, still, in 1996, Bill Gates created a dedicated team with the sole purpose of bringing TV to the Internet. However, that didn’t work.

The main problem with Gates' vision at the time was that Microsoft had tried to linearly apply TV to the Internet as if the two technologies would follow the same development pattern.

Over the years, streaming took over the Internet (see Netflix), but it evolved in completely different ways and formats (see Netflix binge-watching).

Yet, while Microsoft realized the Internet's potential early on, it executed poorly on it. By 1996, it was clear that "browsing" was the killer commercial application of the Internet, and it had a new king.

A featured in Time Magazine in February 1996, a shoeless Marc Andreessen (at the time 24) was featured as the new king of the Internet, an image that Bill Gates didn't like at all.

The Browser wars

After months of tinkering, a young Marc Andreessen, co-founder of Netscape, and Jim Clark concluded that the next big thing would be a "Mosaic killer."

As the story goes, back in 1994, as Clark had left Silicon Graphics, he had met Marc Andreessen through a common friend, whom Clark recognized right away as a person worth betting on.

Initially, the two brainstormed ideas about potential ventures to start. But suddenly things became clear. They could develop a Mosaic killer. In fact, the initial developers' team (of which Andreessen was part) was now working on other projects (Andreessen had moved to California) as NCSA took credit for the development of Mosaic.

Andreessen, together with Clark, convinced the team of developers who had worked on Mosaic to develop a Mosaic killer from scratch. This would later become Netscape, the most successful Internet browser.

Netscape further improved Mosaic's capabilities. For one thing, Marc Andreessen was a software guy by inclination, and he knew that on the Internet, fast development cycles were the rule.

Things didn't need to be perfect, as new software releases could fix bugs or things that didn't work while quickly gathering users' feedback and making the product way better, not in months but weeks.

This was the new paradigm of the software industry, as the Internet playbook took over. While the first version of Netscape was slightly better than Mosaic, in its later releases, it improved many times over.

By 1997, the browser industry had become a pro game, where Netscape and Microsoft had brought large development teams together. In January 1997, NCSA stopped developing Mosaic.

On the other hand, in 1995, Netscape IPOed, creating the first multi-billion dollar Internet startup.

After only sixteen months of the company's inception, Netscape showed a skyrocketing revenue path, even though its losses kept mounting. Things didn't look better, as Microsoft went all in!

Clark's reasoning was that once Netscape had become the market leader, they could monetize that leadership in the long run through enterprise deals, similarly to how Microsoft had done, thus creating a strong distribution advantage that would last.

While Clark's strategy proved to be correct, as Netscape ramped up its enterprise deals, it also showed Microsoft that they needed to act fast!

By 1995, Microsoft finally launched its browser, Internet Explorer.

To be quick and copy what had already worked for Netscape (Bill Gates's standard playbook, which resembles a lot of Mark Zuckerberg's playbook in the last decade), Microsoft licensed the code of Internet Explorer from NCSA.

In short, Microsoft's codebase to kick off its browser, Internet Explorer, was that of Mosaic, the same browser that, a few years before, Andressen and the core development team had built at NCSA!

One of Marc Andreessen's famous quotes was, "Reduce Windows to a set of poorly debugged device drivers."

Netscape's threat further created a sense of urgency for Microsoft's top leadership, who started to invest massively in its browser. By 1995, Netscape had the most successful browser on the market and had developed it by bringing together the original team of Mosaic. Netscape truly became a Mosaic killer. From over 90% browser market shares of Mosaic in 1994, by 1995-6, the situation had turned upside down.

Netscape had reached 80% of the market share, where Mosaic adoption had stalled (Netscape took a growing pie of the exponentially growing Internet users' base). Netscape did that through fast releases and built-in network effects.

By 1996-98, Internet Explorer, thanks to Microsoft's incredible distribution strength, was stealing market shares from Netscape, thus stealing its market leader position.

Indeed, Microsoft was simply bundling its Internet Explorer within its Office Package, thus making it the default choice for users to browse the Internet. This was nothing new to Microsoft, which had used the "bundling strategy" for years now.

Yet things looked different in the late 1990s. Microsoft was now the undisputed dominant player in the PC industry, and it was trying to stiffen the competition through distribution in the newly formed Internet industry.

The Microsoft bundling strategy would later cost the company a famous antitrust case. In 1998, Bill Gates was called for hours of deposition that drained Gates and might have determined his decision to step down as the company's CEO in 2000.

To be sure, we don't know what really happened backstage in that antitrust case.

I assume that Gates implicitly threatened to leave Microsoft's reins if he wanted to avoid the whole company's breakdown (this is pure speculation on my side).

This was the business context in the late 1990s when Google entered the picture.

If browsers wrecked down the walls of the proprietary networks, search engines completely shattered them

As the number of sites on the Internet grew exponentially (by the year 2000, more than 360 million users had joined it), the need for a tool to surf the web and find the most relevant pages emerged. In parallel to the development of proprietary networks, like AOL, other tools turned out to be congenial to the Internet.

The first was the browser, which became very popular with a player like Mosaic, which has a short time span.

Yet, as we saw, by 1994, a group of young people who had also worked at Mosaic (among them venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, founder of a16z) built a browser called Netscape, which by 1995 became the market leader.

Netscape drew the attention of Microsoft’s Bill Gates, which understood how browsers could become the gatekeepers of the Internet. This spurred a war between Microsoft and Netscape, which culminated in Microsoft’s release of Internet Explorer, bundled in its Microsoft Office products.

Thus, Microsoft leveraged its position in the market to quickly gain market shares against Netscape.

This drew the attention of the regulators who called Microsoft for abusing its dominating position. This led to the parallel development of another commercial killer application: search.

As the Browser wars went on, search became the most important application of the Internet, enabling users to surface the growing numbers of pages on the Web, which was growing at an untamable pace.

Search, therefore, was essential.

However, the first search engines, while helpful, were still too focused on paid placements and also much easier to game by webmasters who could easily have their pages show up as relevant, even if not. This paved the way for new players.

One epitome of that was GoTo.com, created by the legendary Bill Gross. GoTo.com not only mixed paid results as if they were organic results.

It enabled everyone to bid and compete on its advertising platform, making paid search a primary feature. While this model, called CPC, was revolutionary, it was also skewed substantially toward paid vs. organic results. In that period, toward the end of the 1990s, another player had developed a search engine able to index and rank the growing number of web pages.

This was first called Backrub, out of a Ph.D. project at Stanford. Later, it was called Google! Google picked up quickly, becoming de facto the most popular search engine at the time. Its ability enabled websites to rank organically without having to pay.

This opened up an industry of practitioners called SEO (search engine optimization experts), who tried to understand the growing intricacies of search to make their content distributed across the web.

Ranking a site organically had become way more intricate, through PageRank, than before, and SEO over the years would turn into a multi-billion dollar industry.

Initially, Google’s founders were quite skeptical of the advertising model for search engines, as they thought this would be intrinsically biased toward paid ads, thus not giving relevant results.

Yet, over time, they set out to change that.

Therefore, they started to build an advertising machine that could also rank paid results based on various factors. Thus, Google borrowed from the GoTo.com CPC model and improved on it. This formula turned out to be extremely powerful.

Google’s deal that made it the tech giant we know today

While Google’s user base was scaling quickly in its early years. Its advertising machine pieces were assembled later on (between 2001 and 2004).

Thus, in the early years, Google had to rely on business development deals to scale up further, strengthen its position, and become the market leader.

In the early days, Google's destiny was all but determined.

Indeed, in the early years (1998-2000), the company was not profitable, recording only $220K in revenue in 1999 and over $6 million in losses in the same year.

In 1999, Brin and Page were still considering returning to Stanford for their Ph. Ds. Indeed, they approached various competing search engines and platforms, including Excite, which tried to sell Google for $1 million!

Yet, apparently, the Excite executive team eventually didn't go for it, as Google's basic premise was to invite users to click on the blue links the tool offered as search results, thus inviting users to leave their search page and navigate the web.

While this is taken for granted today, back then, most search engines made money by keeping users on their search pages (similar to what Google has evolved into today); thus, Google posed a threat to their business model.

The same deal was rejected by other players like AltaVista and Yahoo.

In 2000, Google had become very popular, yet it still recorded over $14 million in losses on a $19 million turnover. Yet Google was backed by Sequoia Capital, led by John Doerr. Indeed, in 1999, Google received $25 million in equity funding from Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins.

As Larry Page announced at the time:

We are delighted to have venture capitalists of this caliber help us build the company; we plan to aggressively grow the company and the technology to continue providing the best web search experience.

At the time, PageRank solved an equation of 500 million variables and two billion terms to serve proper search results. The market was still small (one hundred million web searches per day compared to the over eight billion web searches.) that today go through Google).

Venture capitalist John Doerr explained in his book Measure What Matters how, in 1999, he placed a $11.8 million bet on Google for 12% of the company.

While Google was not a first-mover (the search engine at the time was the 18th to enter the market, as Doerr explained), two months later, in the new Google offices, Larry Page was lecturing Doerr on the poor quality of the existing search engines' results and how Google would improve, at least 10x, compared to existing players.

As a venture capitalist, Doerr's main job was to guess the potential market size of a new industry (this is the obsession of venture capitalists).

And as the story goes, Doerr posed the question to Larry Page:

How big do you think this could be?

Larry Page responded:

Ten billion dollars.

This seemed a crazy market cap to Doerr, who had considered a potential market size of Google of one billion dollars at most.

So Doerr asked:

You mean market cap, right?"

And Page swiftly replied,

No, I don't mean market cap, I mean revenues.

That seemed crazy enough to Doerr, as with ten billion in revenues, Google would be worth at least a hundred billion in market cap, which was the size of Microsoft, IBM, or Intel at the time.

Six years later, to that conversation, by 2005, Google had reached a hundred billion market cap. By 2021, the Google advertising machine would generate twice that in revenues alone, making Google (now called Alphabet) a 1.8 trillion dollar company!

The deal with AOL was among the most important deals Google sealed in the early years. Indeed, AOL saw search as a feature within its proprietary network, thus featuring a search engine that enabled users to surf the web.

Initially, GoTo.com (later called Overture) had a deal with AOL to be featured as the leading search engine. Yet, as this contract expired in the late 90s, Google jumped on it, managing to get the deal with AOL instead of Overture! This deal was a very important one, which put Google on a further growth trajectory.

Over the years and into the early 2000s, proprietary networks have become less relevant as more Internet/Web players have spurred up. From e-commerce to search, platforms like AOL have lost traction. In that scenario, Google became the new King in town.

From then on Google became the new dominant player on the Internet. From wrecking the walls of closed proprietary networks.

Over the years (from the 2010s – to the present), Google, then became Alphabet, turned into a sort of Walled Garden. Is being a first-mover no longer the trick?

Technologies can give an essential advantage in the concise term. However, those advantages can be lost quickly if technology is not leveraged quickly. Yet implementing new, unproven technology is also risky, initially very expensive, and often requires the ability to develop a whole new market.

To make things worse, even when this new market has been developed, that doesn’t give you a long-term competitive advantage. New players who come in can do the same by simply copying part of the strategy that turned out to be successful.

In short, the first player laid the foundation for the latecomers to leverage the existing technology and improve on it to gain an advantage. But if being first does not give a long-term advantage, what’s the key ingredient there?

The value of network effects

From the rise of Microsoft onwards, many tech companies understood the value of a platform strategy. A platform strategy creates value for users by enabling an entrepreneurial ecosystem on top of it.

The essence of network effects stands in the fact that the service becomes exponentially more valuable for each additional user as more users join in. Of course, building network effects isn’t easy either. Many platforms like Uber and Airbnb figured out at the beginning when they needed to understand how to kick off these networks’ effects.

Thus, when it comes to creating a lasting competitive advantage in this digital landscape, even if you are a first-mover, you have to think in terms of network effects.

The first-scaler advantage matters only if you can dominate a market in the long-term

When Netscape built the most valuable commercial browser back in the mid-90s, the company gave up profits to grow as quickly as possible.

The bet was if Netscape grew large enough to have the most shares of the browsers market it could eventually enjoy also wide profit margins in the long term.

Yet, Netscape awoke Microsoft too early. While Microsoft did leverage its dominating position to crush Netscape, it also managed to destroy its market leadership over time. Indeed, while Netscape became a multi-billion dollar success, it never turned a profit, and it eventually sold to AOL as the pressure from Microsoft was becoming unsustainable.

Thus, even when you do scale, and you do it first, you still need to make sure to stably control that market. Otherwise, like in the case of Netscape vs. Microsoft, you might be taken over. Of course, in this case, Netscape was crashed by a tech monopoly that took advantage of its dominating position. And Microsoft would pay that many times over.

In fact, while the company survived the subsequent waves of the Internet, it was substantially slowed down by the antitrust case, which would be a threat to Microsoft for years. Today, under the change in leadership and the direction of Satya Nadella, Microsoft has also become an over two trillion-dollar company.

Changing business playbooks

When browsing took over the early Internet, that was quite unexpected for many. Also, brilliant people like Bill Gates had envisioned a more linear evolution of the Internet, almost as if that was supposed to bring TV online.

While this vision would be partially realized through the 2010s (see Netflix), it also shows that the entertainment model on the Internet evolved in a very different way than TV.

The same applied to search. When Google took over, existing giants like AOL, who had successfully dominated in the previous decade, were taken aback by the success of the latecomers in the Internet revolution.

First, players like AOL thought that search was not a commercial killer application but rather a feature to be added to their services.

Second, they didn’t necessarily envision how search engines would change the whole Internet playbook altogether. No more, based on conventional marketing, a tool like Google took over, as it combined product, marketing, and distribution as if they were a whole.

Third, even when consumers quickly switched to these new tools, it was very difficult to acknowledge existing/dominant players.

In short, things might work the same for a long time and then suddenly change. And when things change, they do it so quickly that the dominant market position might be swept away quickly.

Google: the King of the Web 1.0

Back in the day, Brin and Page didn’t hide their resentment toward the advertising business model, which was the prevalent model for search.

Indeed, in the paper “The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine,” Page and Brin presented their prototype of Google.

With a full-text and hyperlink database of at least 24 million pages, they explained, in a paragraph dedicated to advertising, “We expect that advertising-funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers.“

The main issue they had with advertising was that it was biased and caused a lot of spam in search results. Indeed, when they met Bill Gross, founder of GoTo, which would later become Overture, the encounter might not have been among the most cordial.

That’s because Bill Gross figured the advertising market had massive potential. He introduced an auction-based system for bidding businesses based on performance and clicks.

However, this was still back when Page and Brin were two academics completing their Ph.D. at Stanford University. The transition to becoming entrepreneurs would take a long time to arrive. Indeed, as venture money was soon to be over, a plan B was needed.

In addition, as Google managed to rank advertising based on relevance (for instance, by ranking those ads that got more clicks), advertising became a possible option. As Larry Page pointed out in the first Google letter to shareholders:

Advertising is our principal source of revenue, and the ads we provide are relevant and valuable rather than intrusive and annoying.

Google revenues started to take off, yet the company would take a few years to become a “unicorn”

By 2000, Google was already a key player in the search industry. However, it wasn’t yet in the safe zone at a financial level. Indeed, in 2000, Google made $20 million in revenue. Even though it had launched its AdWords network, which would allow it to speed up its growth Google's business model was still transitioning.

Some pieces of the puzzle were still missing. However, the first massive deal came into the door.

Overture was the father of pay-per-click advertising

By the end of the 1990s Bill Gross, founder of Idealab, an incubator where he could execute all his ideas, had also founded GoTo a search engine that for the first time used the pay-per-click business model.

In other words, in the past, web portals like AOL or Yahoo just sent undifferentiated traffic to websites. GoTo introduced a different logic: the business gets paid for advertising only when users click through it, thus only when there is relevant traffic.

The logic behind the GoTo business model might seem trivial today, but it was revolutionary at the time. In fact, with his pay-per-click Bill Gross would buy undifferentiated traffic from web portals at a low cost and sell that traffic for a much higher price.

GoTo soon changed its name to Overture, while GoTo was both a search engine and an advertising network.

Instead, Overture became merely an advertising network able to arbitrage the price difference between undifferentiated traffic and qualified traffic. Thus, Overture was the first to invent and prove that pay-per-click would be the business model of the Internet.

At the time, AOL was among the most prominent web portals and among the most significant deals Overture had closed for its distribution strategy. Although Google was growing at a super-fast speed, it wasn’t any closer to becoming the market dominator it would soon become.

Google copied - part of - Overture's business model and stole the AOL deal

By 2002, Google had finally launched its Google AdWords network, which replicated that pay-per-click business model and improved on it.

It also figured out that if he wanted to scale up fast, it had to close large deals with web portals like AOL. Nowadays, AOL doesn’t sound to be important.

At the time, it was among the most popular web portals.

Known as America Online in 1998, it purchased Netscape, the dominant browser of that time. In short, there was a time when AOL was almost synonymous with the Internet.

In May 2002, the deal between AOL and Overture was expiring, and Google needed to take swift action.

As reported in the book Googled: The End of the World As We Know It, Page said about the AOL deal, “I want us to bid to win,” while Kordestani, in charge of business development and sales, warned, “You’re betting the company if you do that.” According to Auletta's account in the book, Page replied to Kordestani, “We should be able to monetize the pages; if not, we deserve to go out of business.”

Whether or not those words are accurate, that deal points out a critical aspect. At that point, Page and Brin were not only the engineers who had created PageRank but, most of all, shrewd entrepreneurs who understood the importance of closing the right deals to kill competitors and dominate the market!

Overture sued for patent infringement then Yahoo settled the lawsuit with Google

Not long after the adoption of Google AdWord Overture sued it for patent infringement. The claim was that Google had copied the Overture model. However, after losing the AOL deal

Overture stock plunged 36 percent to $21.99. Although the company continued to make high-profit margins, it would never recover from that. In fact, in 2003, Yahoo bought Overture for $1.63 billion, valuing it at $24.63, roughly a 15 percent premium to its closing price at the time of the deal.

Now part of Yahoo, Google settled the Overture dispute in 2004. As reported in the NY Times, “Google agreed to give Yahoo 2.7 million shares, worth $291 million to $365 million, if the shares sell within the range of $108 to $135 that Google has estimated for its initial offering price.”

It was the end of Overture and the rise of the most influential tech giant, today worth more than eight hundred billion dollars.

Google was primarily targeting AdSense technology from Applied Semantics. It was the missing piece of the puzzle. In fact, with AdSense, Google could finally offer targeted ads on the websites of partners who joined the program.

In short, Google would allow businesses to show their banners on the estate of those blogs that had become the heart of the web in the 2000s.

It would also allow those blogs to transition from amateurs to making money via advertising. It was all tracked and based on the page's context.

The AdSense value proposition was quite compelling. As pointed out in a 2004 financial report Google would “generate revenue by delivering relevant, cost-effective online advertising. Businesses use the AdWords program to promote their products and services with targeted advertising. Also, the thousands of third-party websites that comprise our Google Network use our Google AdSense program to deliver relevant ads that generate revenue and enhance the user experience.“

AdSense would become a critical part of the business.

Google embraced the whole web with its business model

At that stage, Google was ready to take off. Back in 2003, when Google had finally fine-tuned its business model, it had three primary constituencies:

Users: Google provided products and services that enabled them to find any information quickly.

Advertisers: The Google AdWords program, an auction-based advertising program, allows businesses to deliver ads both to customers on Google sites (for instance, the search page) and through the Google Network (any blog or site part of the AdSense program).

Websites: Google free products, Google AdWords, and Google AdSense embraced the whole web. Users get information for free and quickly. Businesses could make money by sponsoring their products on Google and via the Google network. Publishers could also quickly monetize their content.

Once the business model had all the pieces, needed growth became the norm. If at all, Page and Brin had to make sure not to have Google implode for hypergrowth. Thus, the most complex challenge might have been managing hypergrowth that would continue for over two decades.

In 2014, Google restructured the company as Alphabet, with Google as a subsidiary. Beyond Search, today, Alphabet offers services like YouTube, Maps, Play, Gmail, Android, and Chrome to billions of people worldwide.

The Google business model is much more diversified today than it was in 2000. By 2017, Advertising still represented 86% of its revenues. Google—now Alphabet—also devoted part of its revenues to investing in bets that might become its next cash cow. Today, those bets only represent over 1% of the total Google turnover.

In 2017, in the founders’ letter, Google explained how it started to roll out AI for several aspects comprised of its products:

understand images in Google Photos;

enable Waymo cars to recognize and distinguish objects safely;

significantly improve sound and camera quality in hardware;

understand and produce speech for Google Home;

translate over 100 languages in Google Translate;

caption over a billion videos in 10 languages on YouTube;

improve the efficiency of data centers;

suggest short replies to emails;

help doctors diagnose diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy;

discover new planetary systems;

create better neural networks (AutoML);

… and much more.

By 2019, Google confirmed its "AI-first" strategy. Indeed, on a stage at the Google I/O conference, Pichai highlighted:

We are moving from a company that helps you find answers to a company that helps you get things done. We want our products to work harder for you in the context of your job, your home, and your life.

This change was critical, as it changed the company's mission from "organizing the world's information and making it universally accessible and useful" to "helping you get things done."

This is a critical move from a business standpoint, as Google highlighted its focus on generating revenues based on its productivity tools—the segment that for decades had helped Microsoft remain among the largest tech players.

No wonder then, that Google free tools play a key role in that.

Today, Google employs sophisticated language models trained on billions of parameters, which might be used in the future to enable the search engine to generate more and more specific answers to users' queries.

Let's keep in mind that, almost 25 years after the company's inception, Google still has many challenges ahead.

What’s next?

In the next edition, we’ll tackle the history of Google, OpenAI, and beyond!

Key Highlights of the Evolution of the Web and AI Trends

The Origins of Google

Academic Beginnings:

Sergey Brin and Larry Page developed "BackRub" in 1996, leveraging backlinks to rank web pages.

Their frustrations with ad-based search engines led to the creation of Google in 1998.

Early academic skepticism of advertising influenced their later innovations in ad relevance.

Early Struggles:

Google sought buyers, offering itself to Excite for $1M, but was rejected.

Backed by Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins, Google raised $25M to scale its technology.

The First Wave of the Internet (1994-1999)

Proprietary Networks:

AOL, Prodigy, and CompuServe dominated with "walled gardens," offering controlled services like email and forums.

AOL peaked in 1999 with a $200B market cap and 23M subscribers.

Challenges and Decline:

The rise of open protocols and broadband exposed infrastructure limitations.

The AOL-Time Warner merger in 2000, valued at $111B, failed due to cultural mismatches and the dot-com crash.

The Rise of Browsers

From Mosaic to Netscape:

Mosaic (1993) introduced visual web browsing, paving the way for Netscape, which dominated by 1995.

Netscape's IPO marked the first billion-dollar Internet startup.

Microsoft's Response:

Microsoft launched Internet Explorer, bundling it with Windows to dominate the browser market.

The aggressive strategy led to antitrust scrutiny but secured Microsoft’s position.

Search as a Killer Application

Search Evolution:

Early search engines focused on paid results, creating opportunities for innovation.

Google’s PageRank revolutionized search with organic, relevance-based rankings.

Advertising Breakthrough:

Inspired by GoTo.com’s pay-per-click model, Google launched AdWords, integrating relevance into ad rankings.

AdSense allowed Google to monetize third-party websites.

Google’s Transformation

Key Deals and Acquisitions:

The AOL deal in 2002 helped Google scale, replacing Overture as AOL's search provider.

The acquisition of Applied Semantics (AdSense) enabled targeted contextual advertising.

Dominance in Web 1.0:

Google transitioned from “organizing the world's information” to productivity and AI with tools like Gmail, Maps, and YouTube.

By 2021, Google generated $257B in revenue, with advertising contributing 81%.

Lessons from the Web Evolution

First-Mover vs. First-Scaler:

Netscape was an early leader but failed to sustain its advantage due to Microsoft's distribution power.

Google’s scalability and strategic partnerships established its lasting dominance.

Platform Strategy:

Successful companies leveraged network effects to create value ecosystems (e.g., Google’s ad network).

Adaptation and Innovation:

Google’s shift to AI and productivity tools showcased its ability to pivot in a changing digital landscape.

AI Trends and the Road Ahead

AI Scaling:

Concerns over innovation plateaus are countered by advancements like synthetic data and improved architectures.

OpenAI and Generative Models:

OpenAI’s GPT models revolutionized AI, with ChatGPT becoming the 8th most-visited website globally by late 2024.

The Future of the Internet:

AI will drive the next wave of innovation, transitioning from traditional search to task-oriented AI.

Read also

Ciao!

With ♥️ Gennaro, FourWeekMBA