This Week In AI Business: AI’s Rare Earth Problem [Week #41-2025]

Many are looking at the “AI bubble” from the wrong perspective. In fact, it’s not that AI is a bubble in the sense that there is a lack of demand; I’ve explained over and over how that’s not the case, and it’s what makes this tech supercyche quite unique.

Instead, and this is the key point: the supply chain of AI is highly fragile, and anything in there can break, at any moment, making the bubble pop, but not for overinvestments, but rather for the lack of a supply chain, solid enough, to enable us to have the computational needs, to serve AI at a mass scale.

In short, the supply chain of AI is so interconnected, interdependent, complex, and dependent on so many actors (contrary to common belief, that’s all in the hands of a few players), that it also has many chokepoints.

Indeed, remember that for every lithography machine produced, there are probably thousands of small suppliers, providing the tiniest components to make it possible.

For every rare earth material that goes into the supply chain of an AI chip, thousands of refineries make it happen.

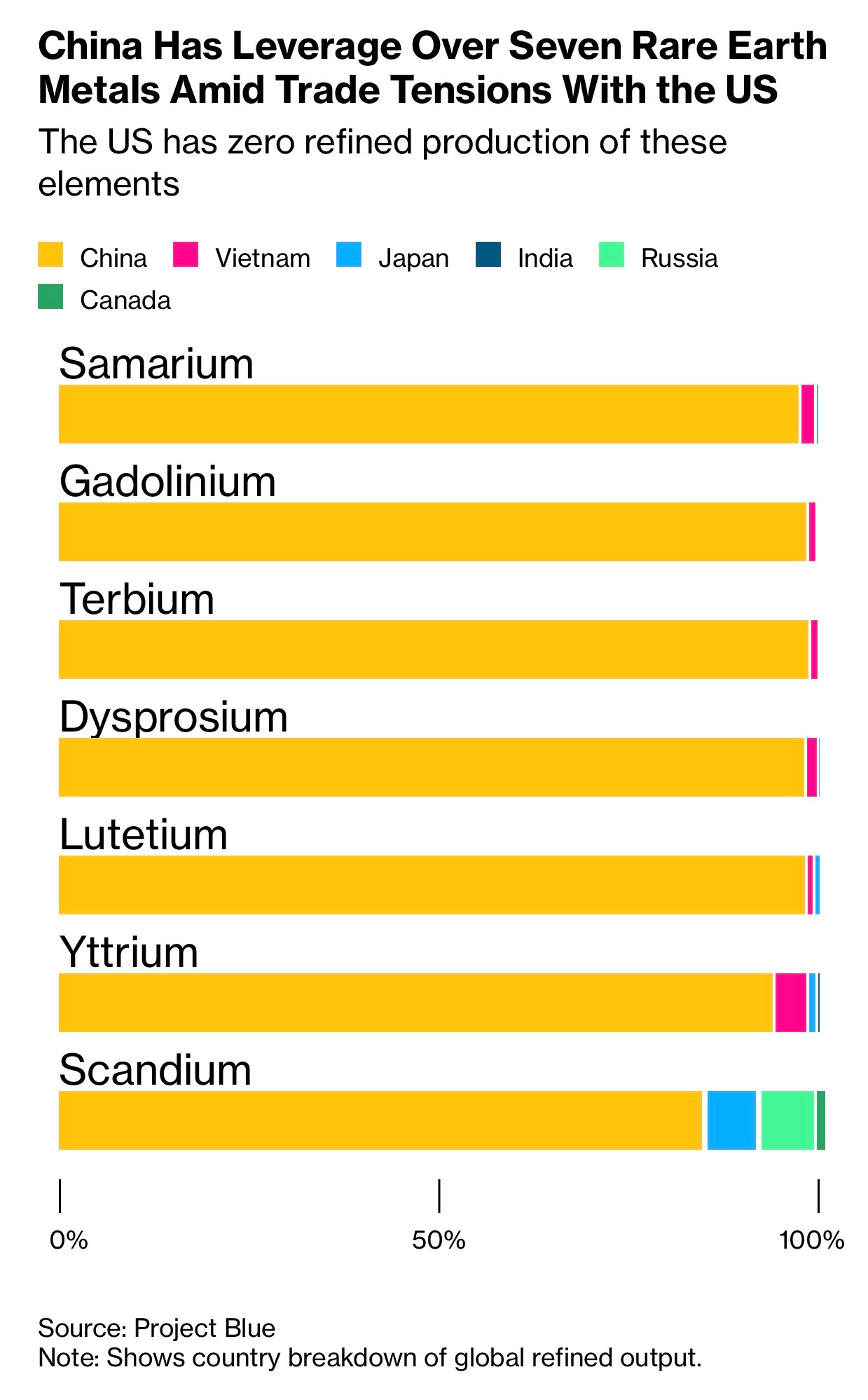

China’s new rare-earth export restrictions have exposed the most hidden and yet most critical chokepoints of the AI supply chain.

In short, China has ruled out that global companies selling goods with certain rare-earth materials sourced from China, accounting for 0.1% or more of the product’s value, must seek permission from Beijing.

Tech companies will probably find it extremely difficult to show that their chips, the equipment needed to make them, and other components fall below this threshold.

This isn’t just another tariff escalation or trade negotiation tactic. It’s a precision-engineered attack on the one supply chain vulnerability that could actually collapse the AI revolution: the physical materials required to manufacture and operate the computational infrastructure that powers everything from data centers to semiconductors to the machines that make semiconductors.

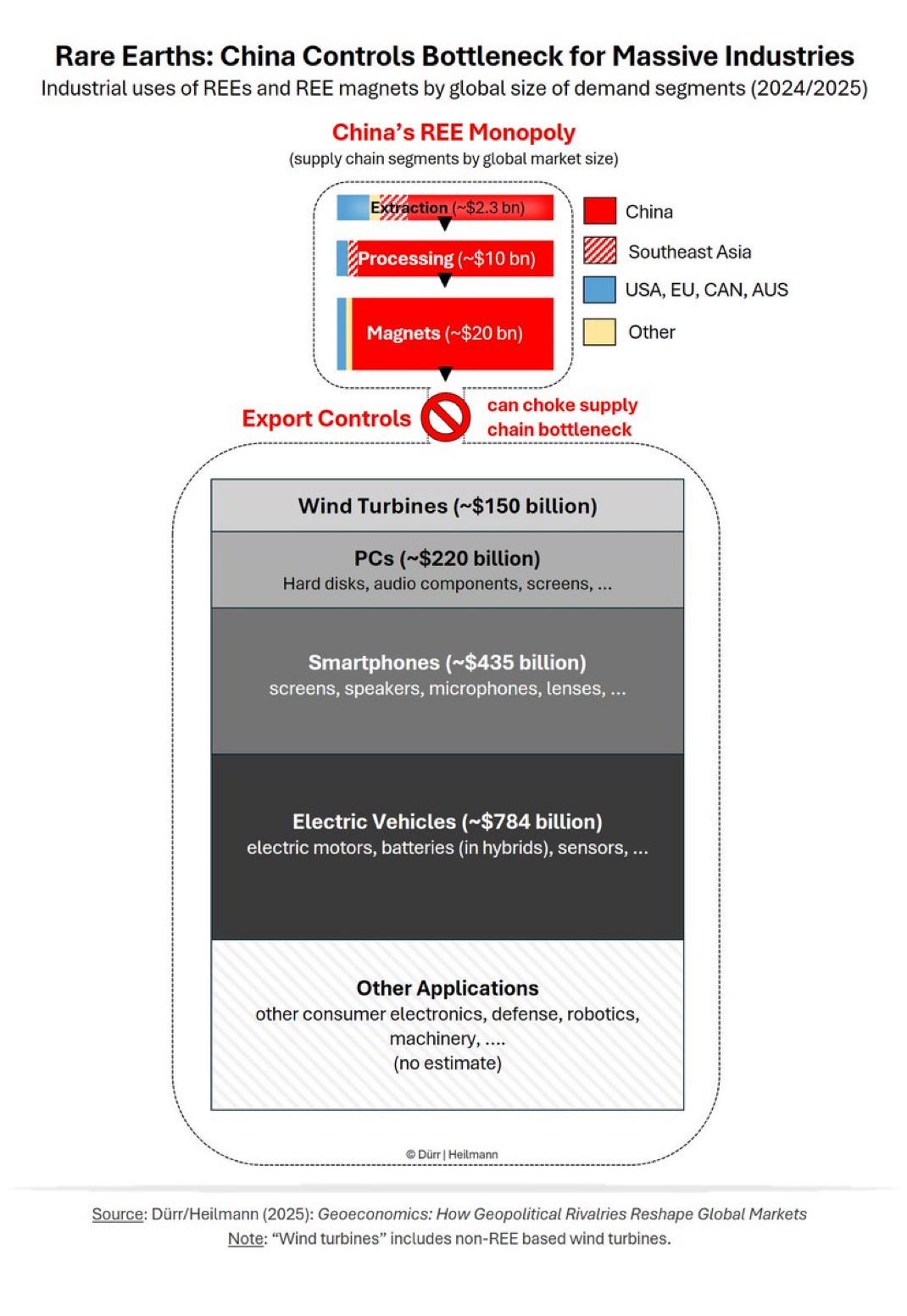

While everyone focuses on semiconductor manufacturing capacity, chip design talent, and AI model capabilities, China produces roughly 90% of the world’s rare-earth materials. These minerals and the ability to refine them are the basis of modern civilization. The rules could cause a U.S. recession if implemented aggressively because of how vital AI capital spending is to the economy.

This analysis examines why rare earths are the ultimate supply chain chokepoint, the structural dependencies that make this threat unique, how this accelerates US-China decoupling and geopolitical realignment, the cascade effects across the AI infrastructure stack, strategic responses, and why most will fail, and the winners and losers in a rare-earth-constrained world

Understanding the Chokepoint

The Material Reality of AI Infrastructure

AI isn’t virtual. It’s deeply physical. And that physicality creates dependencies that can’t be coded around, negotiated away, or venture-funded into existence.

Every layer of the AI stack depends on rare earths.

Data centers—the foundation of AI inference and training—require permanent magnets (neodymium, dysprosium) in hard drives, cooling fans, and power supplies. Their fiber optic networks need erbium and ytterbium for optical amplification. Power systems rely on rare earth magnets in generators and transformers. Even cooling infrastructure uses europium in phosphors for efficiency monitoring.

Semiconductors—the processors running AI models—depend on rare earths at every step. Chemical-mechanical polishing uses cerium oxide slurries to flatten wafer surfaces. Phosphors and dopants (yttrium, lanthanum) determine chip performance characteristics. Epitaxial growth requires various rare earths as catalysts and dopants. Advanced packaging uses bonding materials containing rare earth elements.

Chipmaking equipment—ASML lithography machines, Applied Materials deposition tools—cannot function without rare earths. Extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography lasers use precision optics made from rare earth elements. Vacuum systems need rare earth magnets in pumps and motors. Robotic handling systems require permanent magnets for precision motion control. Measurement and metrology tools depend on rare earth-based sensors and detectors.

The U.S. and other countries are pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into data centers, making AI a key economic engine. China gaining control of the technology would potentially let it catch up in the AI race and upend the world order.

Why This Chokepoint Is Different

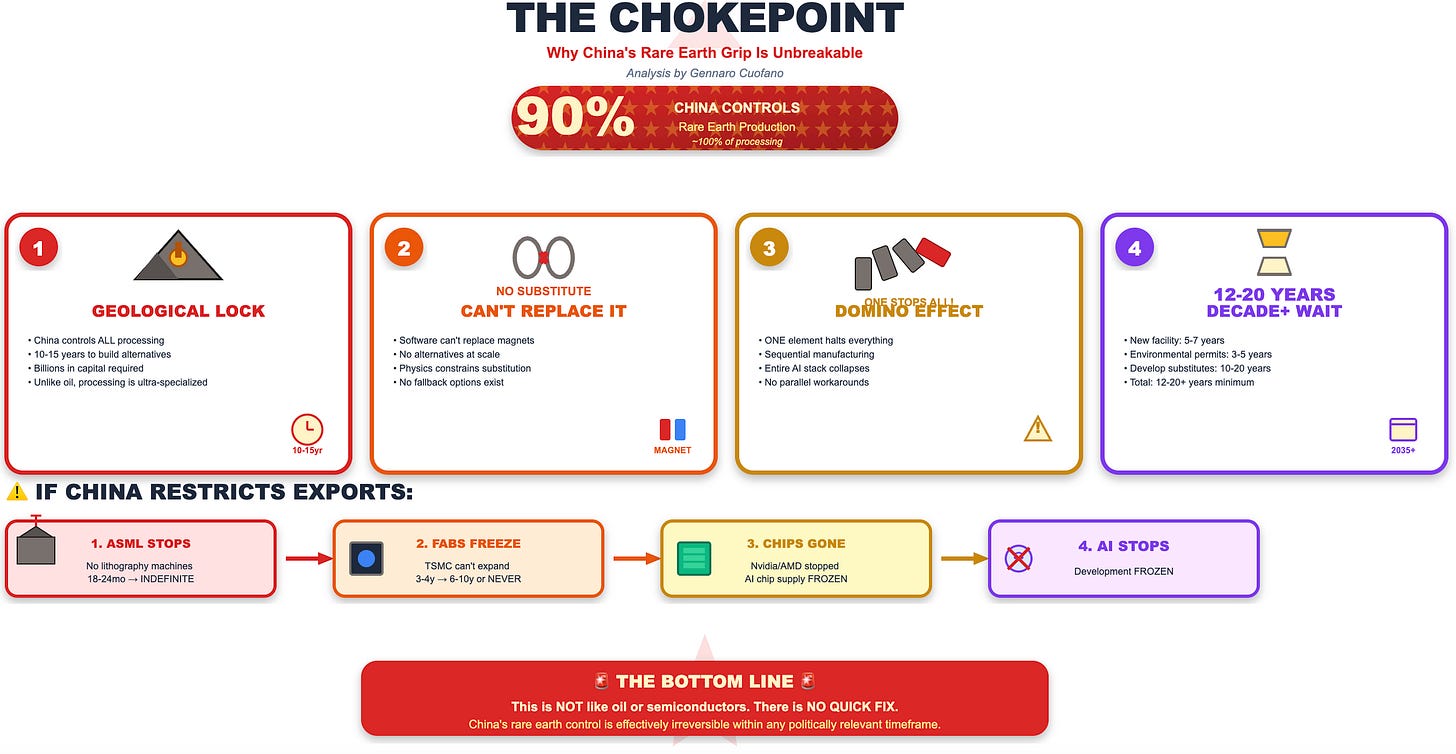

Unlike other supply chain vulnerabilities, rare earth dependencies have four characteristics that make them uniquely threatening.

First: Geological concentration. Rare earth deposits exist globally, but economically viable deposits are concentrated. China controls not just mines but the entire processing and refining infrastructure. China produces roughly 90% of the world’s rare-earth materials. Building alternative processing capacity takes 10-15 years and billions in capital investment.

Second: Technical irreplaceability. You can’t substitute software for magnets. No amount of AI optimization can replace neodymium in a motor. Physical properties of rare earths—magnetic, optical, electronic—have no near-term alternatives. R&D into substitutes has been ongoing for decades with limited success.

Third: Cascade dependencies. One missing rare earth can halt entire production lines. The rule threatens the supply chain for semiconductors, which are the lifeblood of the economy, powering phones, computers and data centers needed to train artificial-intelligence models. Sequential manufacturing means disruption at any point stops everything downstream. You can’t “partial ship” chipmaking equipment missing critical rare earth components.

Fourth: Long lead times. Building new mines takes 7-10 years from discovery to production. Building processing facilities takes 5-7 years. Establishing environmental compliance takes 3-5 years. Developing alternative materials could take decades. Total timeline to establish independent supply chain: 12-20 years minimum.

The combination of these four factors creates what military strategists call a “strategic chokepoint”—a single vulnerability that, if exploited, can cripple an entire system regardless of strength in other areas.

This brings us to today’s structural reality.

The weekly newsletter is in the spirit of what it means to be a Business Engineer:

We always want to ask three core questions:

What’s the shape of the underlying technology that connects the value prop to its product?

What’s the shape of the underlying business that connects the value prop to its distribution?

How does the business survive in the short term while adhering to its long-term vision through transitional business modeling and market dynamics?

These non-linear analyses aim to isolate the short-term buzz and noise, identify the signal, and ensure that the short-term and the long-term can be reconciled.

![This Week In AI Business: AI Technology Bubble Analysis [Week #35-2025]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pkd2!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc6d426bc-a100-44fb-b159-47c64a21662f_1290x1332.png)

![This Week In AI Business: The Tariffs Issue [Week #14-2025]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!gmE2!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F036a61a5-5103-4038-b827-bb2f1edbe8b7_1970x1158.png)