This Week In AI Business: The $200 Billion Catch-Up [Week #36-2025]

In the previous weekly issue, I covered the structural reality that underlies the current “AI Bubble” (characterized by a period of aggressive expansion on the supply side, driven by one of the most incredible adoption tech waves of the last 50 years).

And to be clear, “bubble” here doesn’t just mean that AI is hyped, but rather that the long-term success of it is not granted, as it sits on a weak foundation of an infrastructure that today mostly doesn’t exist, to serve this tech at scale.

To me, it feels the opposite of the web era. Here, we have billions of consumers who are potentially ready to use AI daily, and yet we lack the necessary infrastructure to support them.

It’s almost as if we’re giving people a 56K dial-up modem to access the Internet to download an MP3, when they already want the fiber optic infrastructure to stream YouTube.

Everyone is asking, Who’s going to pay the bill for AI to move to mass adoption? Sure, we’re building the infrastructure with the assumption that the whole world already wants AI, across the board.

But is it true?

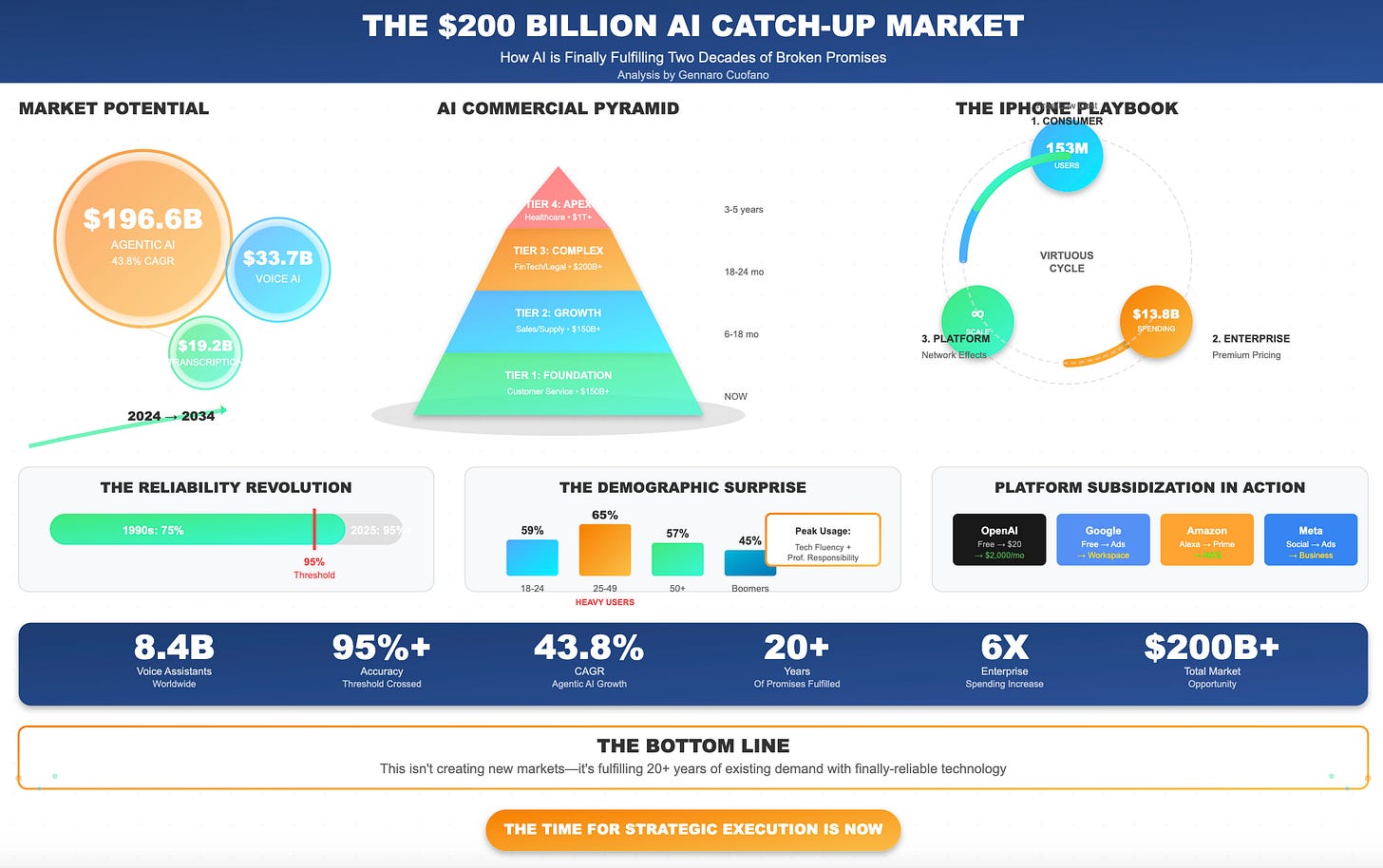

For this issue, I want to address these concerns, and I will not consider the potential and projected demand for the next ten years. But I’ll instead start from something else: the unfulfilled demand for what the web promised, which it couldn’t deliver.

The most profound insight about today's AI revolution isn't what's new—it's what's finally working.

For over two decades, we've carried unfulfilled promises in our collective technological memory: smart voice assistants that truly understand us, transcription that captures nuance, digital helpers that actually help.

These weren't pipe dreams, they were market demands waiting for technology to catch up.

Today's AI boom represents the largest catch-up market in modern history.

With a combined Total Addressable Market exceeding $200 billion across core applications, we're witnessing the economic fulfillment of promises made when most of us were still using dial-up internet.

Top Latest Issues:

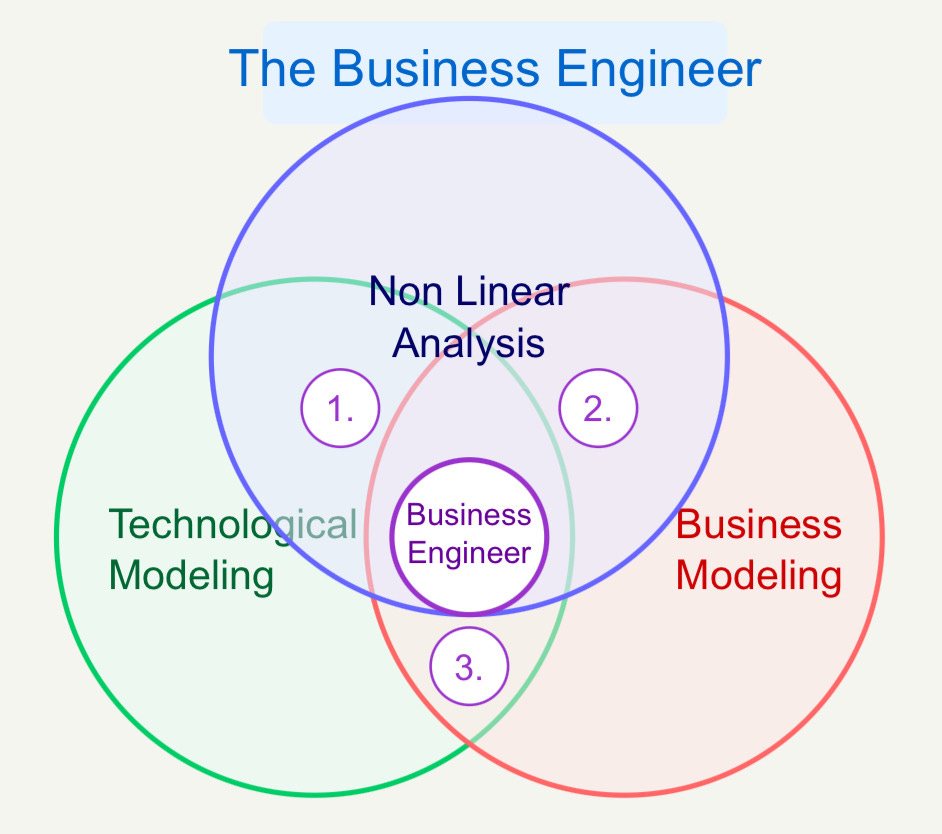

The weekly newsletter is in the spirit of what it means to be a Business Engineer:

We always want to ask three core questions:

What’s the shape of the underlying technology that connects the value prop to its product?

What’s the shape of the underlying business that connects the value prop to its distribution?

How does the business survive in the short term while adhering to its long-term vision through transitional business modeling and market dynamics?

These non-linear analyses aim to isolate the short-term buzz and noise, identify the signal, and ensure that the short-term and the long-term can be reconciled.

![This Week In AI Business: AI Technology Bubble Analysis [Week #35-2025]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pkd2!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc6d426bc-a100-44fb-b159-47c64a21662f_1290x1332.png)